Recently, Jane Dickinson drew attention to the power of the language we use in her blogs examining language and health and in her argument to replace words that shame. It reminded me of another instance of language use that I believe to be inherently harmful – referring to nursing students as student nurses. This practice has been so widely used for so long that I can imagine many gasps and reactions, such as, “Well, that’s what they are; what else should we call them?” Why not nursing students? Is there a difference? I would argue there is a great difference.

I cannot think of one other group of students, health or otherwise, that is referred to with a similar moniker. We do not speak of student doctors, student lawyers, student engineers, for example. They are medical students, law students, engineering students. The lack of parallelism is the first indication that we should examine this practice.

When I “trained” to be a Registered Nurse in a hospital in the early 1960s, student nurses made up a large proportion of the hospital’s workforce. Student nurses were identified by their caps, first having none in the first 6 months, then after the capping ceremony, a white cap. Second year students were identified with a light blue ribbon on their caps, third year meant a dark blue ribbon, until finally Registered Nurses wore the coveted black ribbon. The uniforms likewise differentiated students from Registered Nurses, with graduate nurses wearing all white and students being required to wear a blue dress, with highly starched white bib and apron – all exactly 14” from the floor, regardless of the student’s height (so in class pictures the skirts were exactly at the same length) – along with plastic collar and cuffs. Although I describe the practice of one particular hospital, similar practice were common elsewhere. Student nurses were a category of hospital worker and were, as such, as easily identifiable as housekeeping staff, candy stripers, or Registered Nurses.

I say all of this to make the point that not only did the label “student nurse” make her (with very few males at that time) identifiable, but also indicated something about her place in the organization and the expectations that organization had of her. (I will continue to refer to “her” because, although our class was unusual in that we had 2 males in our class, their uniform was white, like male Registered Nurses wore. It did not change throughout the 3-year program, and neither male students nor male Registered Nurses wore a cap or any other ranking symbol.)

The term student nurse comes from a time when nursing students were expected to be not only subservient (if a physican entered the nursing office, a student nurse who was sitting and charting, for example, was expected to rise and give the physician her seat), but also loyal, innocent and pure. The Florence Nightingale pledge, recited at graduation by the graduating classes of the time, included the promise to “pass my life in purity.” In the first year after my graduation, I was employed as a Registered Nurse at a secular hospital (I ‘trained’ in a Catholic hospital) in a different Canadian province.) Yet the Director of Nursing forbade the graduating class that year from taking the pledge because she didn’t believe they had lived their lives in purity. She enjoyed the power to be able to do that!

This combination of an aura of innocence/ purity with the expectation that student nurses provided intimate care to males made “student nurses” highly desirable as dates. Even during my student nurse years, engineering students from the local university would come to hospital schools of nursing to find dates for their dances. Unfortunately, this also applied to nurses generally – the saying “if you can’t get a date, get a nurse” was common for years after I graduated in 1964. The frequent representation of nurses as sex objects, well documented by such authors as Kalisch and Kalisch extended to student nurses as well.

Despite the fact that nursing education has changed dramatically in the last 50 years, the term “student nurse,” with all its connotations, persists. When I was teaching, I challenged students to refer to themselves as nursing students instead. In class discussions on the topic, despite students’ general agreement that the connotation of “student nurse” was very different from that of nursing student, very few took up that challenge and subsequently submitted assignments in which they referred to themselves as student nurses. Some told me they were required to designate their status as S.N. when signing their charting.

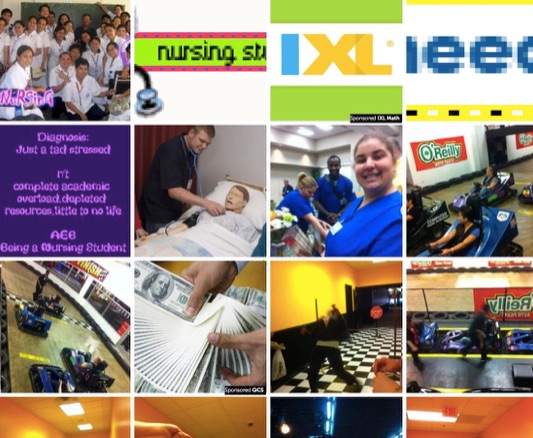

I was interested in whether or not a Google images search for nursing student yielded any different result than search for student nurse images. The screen shots of the first screen that came up with each search are below. Without a careful analysis, some differences are immediately apparent. The top one is the screenshot of student nurse images; the second a screenshot of nursing student images.

While both screenshots include some images that appear unrelated, in the top one they are images of children. There are no images of nurses practicing, and the screenshot includes images of the back of a nurse’s capped head, and the nurse as a romantic figure (Cherry Ames). The somewhat self-deprecating text message reads “ Student Nurse Diagnosis: Stress R/T: knowledge deficit, impaired memory, sleep deprivation, unbalanced nutrition, interrupted family process, lack of social interaction, disturbed energy field.”

Note the general increase in diversity and portrayal of adult nurses providing care in the second picture. The unrelated shots appear to depict Go-Kart racing. The text image, giving the same stress diagnosis, makes its point without self-degradation: “Diagnosis: Just a tad stressed r/t complete academic overload, depleted resources, little or no life.

It seems to me that the collages support the argument that the term student nurse has a different connotation than nursing student and its removal from our lexicon is long overdue. Some time ago I wrote a blog about nurses soaring like eagles. It is a parable about an eagle that finds itself in a chicken yard and starts to act like a chicken, rather than fulfilling its destiny and potential as an eagle. I believe that by referring to nursing students as student nurses we are unwittingly reinforcing the many messages that the term connotes and are hindering their ability to soar like eagles.